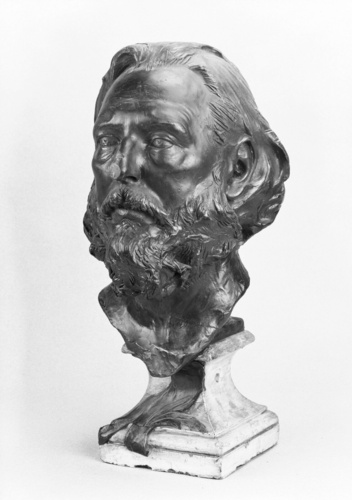

Cache-pot

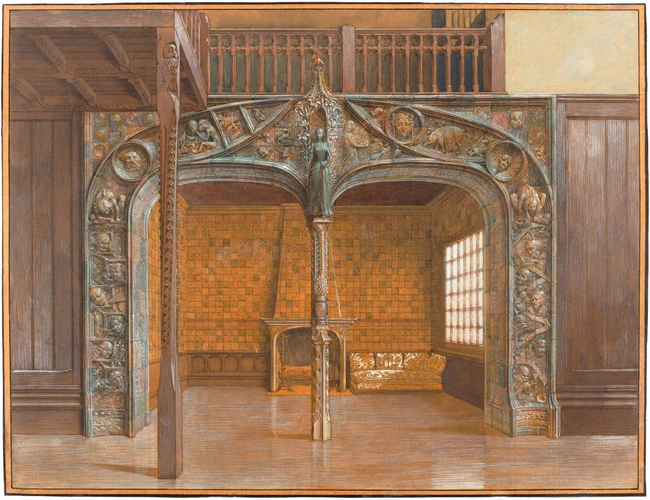

In 1888, the sculptor Jean Carriès (1855-1894) moved to La Puisaye in the Nièvre to devote his time to stoneware. At the time, La Puisaye counted several centres producing utilitarian pottery, glazed or unglazed. After a short stay in Cosne, Carriès settled at Saint Amand where a huge studio soon went up to make the monumental door commissioned by the Princess of Scey-Montbéliard, née Winaretta Singer. But in Spring 1891, while still working at Saint Amand, he increasingly withdrew to the Montriveau manor where he built a kiln to fire his pottery and the stoneware plaques for the door.

The first firing took place on 23 September 1891. Carriès' contributions to the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in spring the following year were enthusiastically received by the public and the authorities because the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts decided to buy a dozen pieces, including this one, for the Musée du Luxembourg and the Musée de Sèvres. Carriès was fascinated by enamelling which he practised alone. The legend of his personal "recipe", carefully nurtured during his life time – for example the reuse of ground bricks impregnated with molten lead or ashes taken from the kilns themselves – contains a grain of truth. But this brilliant lack of method which created some of the finest pieces of Western ceramics was based on close observation of the age-old processes used by the local people and a sound knowledge of modern chemical processes.