Crime and Punishment

Etude de pieds et de mains, 1818-1819

Montpellier, Musée Fabre

© Musée Fabre de Montpellier Agglomération ?R cliché Frédéric Jaulmes" / DR

La justice et la vengeance divine poursuivant le crime, 1815-1818

Saint-Omer, musée de l'hôtel Sandelin

© RMN-Grand Palais / Daniel Arnaudet

Thou shalt not kill

"But what then is capital punishment if not the most premeditated of murders, to which no criminal's deed, however calculated, can be compared". Albert Camus

The first criminal in the history of the human race, Cain, carried his own punishment within him: guilt. This is as much the fruit of his remorse as the implacable judgment of God whose sixth commandment decrees: "Thou shalt not kill".

Cain was a fratricide. He opened the way for crimes and murders of all kinds: patricide, infanticide, regicide and genocide. For evil, introduced into Eden by his parents, is in every person.

Eternally punished and a fugitive, Cain poses the question, beyond that of guilt, of punishment. God did not take his life. To God's commandment and to the grace He accorded Adam's son, man has nevertheless responded with capital punishment.

Justitia, 1857

Paris, maison Victor Hugo

© Maisons de Victor Hugo / Roger-Viollet

1791: Egalitarian Death

During the French Enlightenment, the death penalty was fiercely debated. The abolitionist arguments of Cesare Beccaria were taken up in France, in 1791, in the Constituent Assembly. In May and June 1791, Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau argued for its abolition but, although torture was banned, the death penalty was retained.

In March 1792, it was decided that executions would be carried out by beheading, and that the guillotine, considered to be more reliable and less cruel for the condemned person, would be the instrument of execution.

Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau sur son lit de mort, vers 1825-1835

Musée de la Révolution Française

© Musée Carnavalet / Roger-Viollet

1793: Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau

On 20 January 1793, and after some hesitation, Le Peletier voted for the death of King Louis XVI. He was assassinated that same night, and became "the first martyr of the Revolution".

The Terror reigned in France and executions abounded. The number of executions and the violence involved in separating the head (did it retain its consciousness?) from the body (did it retain a capacity to move?) was a subject of fascination for artists. Alexander Dumas recounted the following, "I have seen criminals beheaded by the executioner, get up headless from where they were lying, and stumble off to fall down ten paces away".

Marat assassiné ! 13 juillet 1793, 8h du soir, 1880

Roubaix, La piscine, musée d'art et d'industrie

© Photographie Arnaud Loubry

1793: The Assassination of Marat

At the height of the Terror, on July 13 1793, Charlotte Corday stabbed Marat, Convention member and "Friend of the People". A martyr of the Revolution, his death was portrayed by David, who invented a new and revolutionary model, taking his inspiration from the conventions of religious painting.

The character of Charlotte Corday equally aroused passions: a treacherous criminal to the Revolutionaries, to the Royalists she was a new Joan of Arc, or a woman who was a victim of her moods. Her legend persists into the 20th century: she is the creature who threatens and kills man; she reverses the roles of martyr and executioner.

Les assassins portent le corps de Fualdès vers l'Aveyron, vers 1818

Paris, Musée des Beaux-Arts

© RMN-Grand Palais / Jacques Quecq d'Henripret

1817: The Fualdès Affair

With his drawings of the assassination of Fualdès (a former Deputy of the Aveyron whose throat was cut in a sordid affair in Rodez on 19 March 1817), Géricault attempted to raise a news item to the scale of a historic event.

The crime, the victim, the murderers, seemed to him, for a while, to be truly epic. This attraction for expressing the dark side of human passions did not however result in a Salon painting. The painter realised that he could not invent anything better than the newspaper illustrators who covered the incident, and that there was nothing noble about this vile execution.

Cannibales préparant leurs victimes, vers 1800-1808

Besançon, musée des Beaux-Arts

© RMN-Grand Palais / Agence Bulloz

Romantic Figures of Crime

The Romantics were fond of bandits, witches, and femmes fatales who either embodied a kind of society outside society, governed by their own codes (honour, vengeance, etc), or embodied irrational and uncontrollable passions.

The Spanish artist Goya, who lived through the bloody occupation of his country by Napoleon's troops, presented different aspects of these figures in his paintings and engravings.

The picaresque and eulogistic nature of the adventures of Brother Pedro becomes both horrific and sublime in his scenes of brigands. His engravings Los Caprichos and Los Ensayos with their parade of witches and malevolent images have encouraged artists, from Redon to Kubin, by way of Schwabe and Klinger, to put forward a black vision of art.

Tête décapitée de Fieschi, 1836

Orléans, musée des Beaux-Arts

© Musée des Beaux-arts d'Orléans, cliché François Lauginie

The Face of the Criminal

Giuseppe Fieschi was executed in 1836 for attempted regicide on Louis-Philippe. His head was painted and modelled according to a documentary practice that was prevalent throughout Europe. Experts in phrenology and physiognomy, disciples of Gall and Lavater, studied the shape of his head and the features of his face, searching for signs of his criminal impulses.

Anxious to distinguish criminals from the insane (who are not responsible for their actions), Doctor Georget asked Géricault to paint a portrait of some monomaniacs. The painter captured all their ambiguity. Their humanity is unbearably present but their eyes are evasive, refusing any communication.

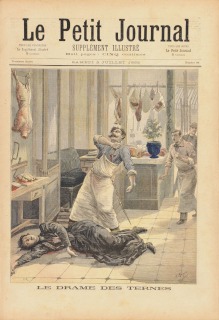

Le drame des Ternes, Supplément illustré du Petit Journal, 1892

Paris, MuCEM, Musée des Civilisations de l'Europe et de la Méditerranée

© MuCEM dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image MuCEM

1880-1920: Tabloids and Violent Crime

The appearance of the popular press, of which Le petit Journal launched in 1866, is the most famous example, provided an extensive audience for all the crimes and incidents which until then had been mentioned in the news sheets hawked throughout France. Pandering to the lowest passions of its readers with spectacular accounts and illustrations, these newspapers circulated, as Balzac put it: "far better novels than Walter Scott's, and which end horribly with real blood rather than ink. "These newspapers were both denounced and defended.

When he started up the tabloid Détective, in 1928, Joseph Kessel declared: "Crime exists, it is a reality, and in order to protect oneself from it, information is better than silence". The presentation of these reviews that brought suspense, drama, precision, cruelty, perversity, latent eroticism etc. to the articles and the images, contaminated the accounts by writers, by illustrators like Rops, and by artists like Klinger.

The illustrated press was also used, by artists like Daumier and Steinlen, to denounce the tragedy of those poor people, ground down by a pitiless world.

Le Pardon, 1865-1867

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

© DR

The Legal Profession

Daumier also chose to present the world of the justice system. Lawyers full of their own importance, judges incapable of any compassion ("The velvet paws of the judge conceal the claws of the executioner" wrote Victor Hugo), victims and/or defendants without hope: the caricaturist's vision is scathing.

Prison du Cherche-Midi, 1903

Paris, Ecole nationale supérieure des beaux-arts (ENSBA)

© Ecole nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, Paris

The Panopticon / The Gaol

It was to put an end to the dark dungeons where prisoners crouched in a bestial or foetal state as represented by Goya and Redon, that Jeremy Bentham invented the Panopticon. This was a utopian architectural system whereby every man was subject to permanent surveillance from a central point by just one other person. This invention, that seemed to represent progress, also offered a view of the world where all actions are controlled.

Bentham's model was installed in France in 1827, without, however, replacing the prisons, like Sainte-Pélagie women's prison from which Steinlen produced a series of illustrations and where between 5 and 10 women prisoners would be crammed into one cell.

Ecce, le pendu, 1854

Paris, Maison Victor Hugo

© Maisons de Victor Hugo / Roger-Viollet

The Death Penalty

The writings, discussions and drawings of Victor Hugo no doubt put forward the most passionate and strongest arguments against the death penalty that the 19th century had ever seen.

Carried out according to a ritual that an artist like Emile Friant reproduced with curiosity and in great detail, or that others like Toulouse-Lautrec or Félix Vallotton reproduced in all its terror, capital punishment and its condemnation were prominent in the artistic debate until Warhol who, showing only the electric chair, without executioner or prisoner, summed up the mute horror of all executions.

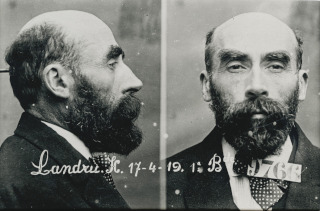

Désiré Landru, 1919

Paris, Collection particulière

© DR

Crime and Science

In the age of Positivism, science turned its attention to criminals with the certainty that crime could be explained, and that the criminal could be understood.

Benedict-Augustin Morel established the theory of degeneration, which called into question the theory of free will. This theory underlies Criminal Physiognomies and Little Dancer aged Fourteen by Degas. Young boys, like Abadie, Knobloch and Krial, whose trial the artist attended in 1880, raised in popular, working class areas of Paris become murderers. The little opera rat, with a similar background, becomes a prostitute.

Thus the question is raised about responsibility for evil. Punishment or rehabilitation?

Alphonse Bertillon put forward the bases for criminal identification. This system involved picking out recidivists using front view and profile photographs and noting the characteristics that do not change (colour of iris, tattoos, etc) then arranging this data, no longer alphabetically but according to physical criteria. The physical identity took precedence over the nature of the individual.

What shall we do for the rent ? ou Summer Afternoon, 1907-1909

© DR

Artists, Madmen and Criminals

Cesare Lombroso, in Genius and Madness, published in 1877, pointed out "the analogy of the epileptic seizure with the moment of inspiration".

In the same way, Patricia Cornwell tried to turn Walter Sickert, who on several occasions had painted prostitutes in their rooms in the Camden Town area of London, into the infamous murderer, Jack the Ripper.

The murderer and the artist respond to aspirations that are beyond ordinary people.

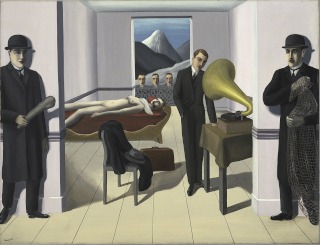

L'assassin menacé, 1927

New York, Museum of Modern Art

© ADAGP, Paris © Digital Image, the MOMA, New York/Scala, Florence

Exquisite Corpses

With different models and different methods, the Surrealists displayed the same fascination with crime and the criminal as the Romantics. Violette Nozières and the Papin sisters were heroines, corpses were exquisite, bodies were contorted, decapitated, with throats cut, etc.

Anything that smacked of order was rejected, and André Breton declared: "The simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down into the street, pistols in hands, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd."