Degas at the Opera

La Loge, 1885

Los Angeles, Hammer Museum

The Armand Hammer Collection, Don de The Armand Hammer Foundation.

© Hammer Museum, Los Angeles / DR

Degas at the Opera

Degas at the Opera

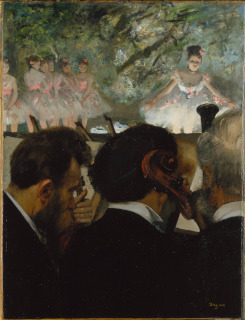

Musiciens à l'orchestre, 1872-1876

Frankfurt am Main, Städel Museum

Städel Museum - U. Edelmann/ARTOTHEK © Städel Museum - ARTOTHEK / Stæ¤del Museum - U. Edelmann/ART

From the 1860s, and until his very last works post-1900, Degas would make the Opera the focal point of his research. He explores its various different spaces (orchestra, stage, boxes, foyer, corridors, dance studios), and scrutinizes the people active in those spaces: ballet dancers (on stage, resting, practising), singers, musicians, audience members, subscribers haunting the backstage area. While he does sometimes cover other subjects, the Opera is an ongoing presence.

This closed realm, whence very little ever leaked through the veiled or dazzlingly bright dance studio windows to the outside world, was a microcosm with infinite possibilities. It allowed myriad experiments, and radiated outward to his entire oeuvre: with multiple viewpoints framing a scene in unexpected ways; various lighting effects, the contrast between the darkened orchestra pit and the brightly-lit theatre, the study of movement and the truth of the gesture, the anomalous assemblage of bodies into those “fine bunches” that Degas was so fond of. The Opera becomes a laboratory in which the broad range of subject matter entails a search for the medium best suited to rendering them, whether it be painting, pastel, drawing, sculpture, engraving, monotype or whatever.

The Opera offers the artist an endless supply of ever ready motifs. But this temple of the fake and the illusion is also a precise equivalent of his art, as Paul Valéry reports: “He always used to say that art is a convention, that the word Art implies the notion of artifice”. Degas states more bluntly: “One sees as one wants to see; this is false; and this falsity constitutes art.” Degas rejects painting from nature, and this transmutation takes place in the studio, filtered by memory, and enriched by his imagination. Hence while his Opera may well appear real, it is never true to life: his orchestras, his views of the auditorium, the stage and behind the scenes, his dance classes and examinations are all phantasmagorical. Degas creates his Opera in the studio. There he devises this open work, eternally dissatisfied he abandons, re-examines, reworks, haunted by the “lofty idea, not of what one is doing, but of what one can do some day in the future”.

Genetics of movements

Genetics of movements

Portrait de Mlle...E[ugénie] F[iocre]: à propos du ballet "La Source", vers 1867-1868

Brooklyn Museum

Don de James H. Post, A. Augustus Healy et John T. Underwood

© Photo Brooklyn Museum

“Ah Giotto! let me see Paris; and you, Paris, let me really see Giotto!” Degas exclaims in a notebook he kept during the years 1867 to 1874, indicating his ambition to become the classic of modernity. His copies from the masters prepare the way for his work on the Opera; his knowledge of the classics pervades his vision of the modern world.

In early youth he built up a huge portfolio of drawings which became a lifelong source of material. His work is characterized by the continuity of his melodic line: the figures studied from the ancients and the ballet dancers share the same dynamic gestures and rhythmic enchaînements. While seemingly spontaneous, the dancers at work and at rest, yawning, massaging an ankle, adjusting a ballet shoe or shoulder strap, revert to the dynamic poses of the models of ancient sculptures and the old masters.

L'orchestre de l'Opéra, vers 1870

Musée d'Orsay

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

See the notice of the artwork

Gestures of expressive suffering and choreographic movements from history paintings and bas-reliefs are turned into mundane poses which breathe life into the dancers and sometimes become visual motifs repeated from various angles. Degas offers a modern take on scenic elements studied among the classics (e.g. cut-off figures emerging in the foreground, architectural lines contributing to the overall dynamics) as part of a contemporary reality. The artist used to say: “the secret is to follow the advice that the masters give us through their works while doing something different from what they did.”

The music circle

The music circle

La répétition de chant, 1872-1873

Washington, DC, Dumbarton Oaks

© Dumbarton Oaks, House Collection, Washington, DC

Degas came from a family background in which music was extremely important. In the 1860s, his father, who came into the family banking business, held a musical salon propagating the new taste for early music, Bach, Rameau, and the painter’s great passion, Gluck. Degas captures the memory of these “Mondays” in the only portrait he ever did of his father, listening intently to the Spanish tenor Lorenzo Pagans.

In the late 1860s, Degas devoted a wonderful set of portraits to the regulars at these evening gatherings of musicians both amateur (his sister Marguerite, an excellent singer; the pianist Blanche Camus) and professional (members of the Opera orchestra). He deploys quite an instrumentarium: guitar, upright piano, grand piano, violin, cello, bassoon, double bass, flute and harp; captures various moments: rehearsal, break, private or public concert; playing all types of music, popular song, solo piano piece, opera duet, symphonic ballet music.

Arlequin, vers 1884

Toulouse, Fondation Bemberg

© RMN-Grand Palais/Fondation Bemberg/Mathieu Rabeau

The portrait commissioned in 1870 by Désiré Dihau, a bassoonist at the Opera, is a key work because it gave the artist his first taste of success, but crucially because the composition of this picture foreshadows many later scenes. Two years after painting the famous dancer Eugénie Fiocre in the ballet from La Source, Degas made the Opera his permanent base. After the war of 1870 and the Commune, he made two versions of Robert le Diable, using the same successful formula. But this was the only time in his work that the performance, an opera by Meyerbeer, is clearly identified.

The Opera, from the Salle Le Peletier to the Palais Garnier

The Opera, from the Salle Le Peletier to the Palais Garnier

La répétition au foyer de la danse, vers 1870-1872

Washington DC, The Phillips Collection

© The Phillips Collection

Degas was familiar with two Paris opera houses: the one on the Rue Peletier, destroyed by fire in 1873, and then, from 1875, the Palais Garnier. But while the man himself was a regular at the present-day Opéra, his work never abandoned the original venue, and haunted it for a long time to come.

Built in 1820-1821, the Le Peletier opera house temporarily replaced the one on the Rue de Richelieu, which was demolished when the Duc de Berry was assassinated after a performance there in 1820. The Salle Le Peletier, adjoining the Hôtel de Choiseul (1716), which served as a backstage and administrative area, was built on the same lines as the old razed building, with many decorative elements salvaged for reuse. While the frontage of this composite whole was always considered unsightly, and the exits inadequate, the public were won over by the auditorium and the stage, for the excellent acoustics and the emergence in the late 1820s of a new repertoire, that of French grand opera.

La Classe de danse, 1873-1876

Washington, DC, The National Gallery of Art

© Washington, DC, The National Gallery of Art ?R NGA IMAGES"

When Degas started working there, the theatre was scheduled for demolition; at the very moment he was starting on his portrait of Eugénie Fiocre, the façade of Charles Garnier’s new Opéra, still under construction, was being unveiled as part of the Universal Exhibition of 1867. When the Salle Le Peletier was burned down in 1873, as the artist was undertaking his very first “ballet scenes” and “dance classes”, he saw his motif literally go up in smoke.

Maybe out of nostalgia for the theatre of his beginnings and its quaint charm, he did not adapt his works in progress to the Palais Garnier architecture Degas disliked this new Opera with its profusion of decorative work, its luxurious foyers and functional backstage area. Another drawback of the Palais Garnier was its being the flagship monument of the Second Empire, a regime that he reviled, exhibiting commissions from artists whom he opposed or despised. While Degas the subscriber was a regular there, the artist spurned it.

House, stage, backstage

House, stage, backstage

La classe de danse, entre 1873 et 1876

Musée d'Orsay

Legs du Comte Isaac de Camondo, 1911

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

See the notice of the artwork

Following the success of his first Opera scenes, in the early 1870s, Degas made the theatre his own, and going backstage from the auditorium, painted his first dance classes. “Exercises in precision” – as he said later, when his failing eyesight was no longer up to the task – using a smooth, even medium, with light impasto in the Dutch style.

After being broken at the barre, under the watchful eye of ballet-master Jules Perrot or Louis Mérante, the dancers would take turns performing their exercises in the middle, “the jetés, balancés, pirouettes, gargouillades, entrechats, fouettés, ronds de jambe, assemblées, pointes, parcours, petits temps, etc.”

Degas never depicts any specific location. The Salle Le Peletier is merely suggested through the odd detail: the Hôtel de Choiseul’s large arched windows and marble pilasters for an imitation 18th century setting. With the slickness of an opera scene-shifter, he alters the layout, opens a trapdoor, adds a staircase, invents recesses...

The scene being played is no less unlikely than the décor, Degas offering a range of “dance examinations” that totally fail to fit in with the known facts. He admits as much to one regular, Albert Hecht: “Have you the power to get the Opera to give me a pass for the day of the dance examination, which, so I have been told, is to be on Thursday? I have done so many of these dance examinations without having seen them that I am a little ashamed of it.”

The instant success of these works secured a clientele for Degas – most notably the baritone Jean-Baptiste Faure – and also enabled him to earn his living through a range of such “products” or “articles” which, like it or not, made him the “painter of dancers”.

“Serious in a frivolous place”, the subscribers

“Serious in a frivolous place”, the subscribers

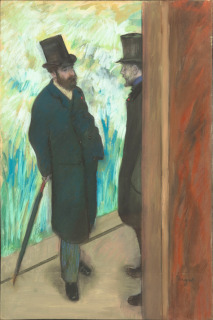

Ludovic Halevy et Albert Boulanger-Cavé dans les coulisses de l'Opéra, en 1879

Musée d'Orsay

Donation sous réserve d'usufruit de Mme Halévy, 1958

photo musée d'Orsay / rmn © RMN-Grand Palais (musee d'Orsay) / Herve Lewandowski / DR

See the notice of the artwork

Ludovic Halévy, a playwright, novelist and co-librettist with Henri Meilhac of Offenbach and his own cousin Bizet, introduced Degas to the Opera in the early 1870s. In return, Degas portrayed him “on stage” in a pastel shown at the fourth “Impressionist Exhibition” (1879). Facing Albert Boulanger-Cavé, a longtime censor of public performance arts, Halévy is in his natural element, compact and dark against a light background, being “serious in a frivolous place”.

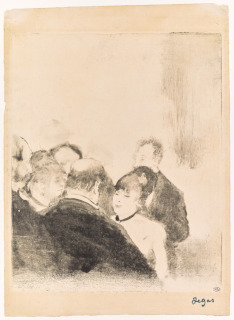

As the typical habitué at the Opera, Halévy found inspiration for a series of best-selling novellas about the amorous adventures of two “petits rats”, Pauline and Virginie Cardinal. Degas liked the crude, caustic, so Parisian tone, and in 1876, after executing his very first monotype with the help of another Opera regular, Ludovic Lepic, he illustrated a few episodes. He selected just a few motifs that lent themselves to this medium, opposing the black of the predatory subscriber and the white of his willing young prey.

Les petites Cardinal parlant à leurs admirateurs, vers 1876 - 1877

Legs Carle Dreyfus, 1952

Adrien Didierjean © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d'Orsay) / Adrien Didierjean

But the Opera was right next door to the brothel. The “Cardinal monotypes” were put to further use in the brothel scenes: dancers and prostitutes, mothers and madams, subscribers and customers; waiting and weariness, small talk, heavy-handed seduction; sofas, armchairs and benches...

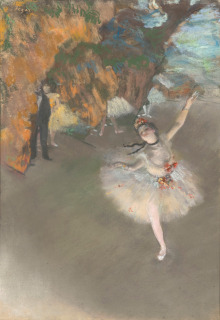

Initially confined to the “Cardinal monotypes”, after 1876 the subscribers and the dancers’ mothers begin to haunt the corridors and lurk behind the scenery. From sitting quietly on tiered seats, the dancers’ mothers are now literally glued to their offspring, forming monstrous groups; the abonnés escape from their confinement in the backstage area, as in The Star, in which, concealed behind a flat, the man is watching his protégée’s solo. Later he actually comes onstage, playing the lead in a show in which the truncated dancers are reduced to supporting roles.

The Opera as technical laboratory

The Opera as technical laboratory

Le Rideau, vers 1881

Washington, DC, The National Gallery of Art

Collection de Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

© Washington, DC, The National Gallery of Art ?R NGA IMAGES" / National Gallery of Art

The Opera was a veritable catalyst and laboratory for Degas’s art as he renewed his approach to media, formats (fans, “tableaux en long”), viewpoints (from above, from below or di sotto in sù ̧ off-centred, askew), and lighting effects.

This was the only world he explored using the gamut of media practised over a lifetime: print (engraving and lithography), photography, pastel, painting (on paper or canvas), sculpture, fans... It was with the Opera that he began to work with monotype and its black-and-white contrasts suitable for expressing the violence of electric lighting, and produced the only sculpture ever exhibited during his lifetime, in wax and composites.

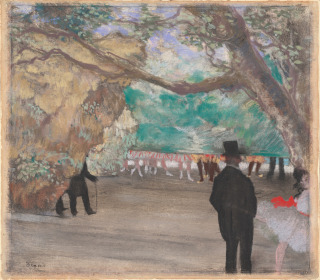

Choristes, en 1877

Musée d'Orsay

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

See the notice of the artwork

His fans turned a fashion accessory seen in theatre boxes into a kind of picture of a shape somewhat resembling the stage. His pastels are often associated with this world of ephemeral beauty, all “distance and makeup”; his paints, à l’essence, metallic and tempera, recall the methods of scenery painters.

Degas would prepare his Opera paintings with an abundance of small sketches in the notebooks and large drawings on tracing-paper, which he tirelessly reworked, and which included squared-up drawings bearing the model’s name and address. These drawings were not always used for any given painting but formed a large formal and experimental pool of material to dip into.

Some, done with a brush in oils diluted with thinner on coloured paper, were exhibited and published during the lifetime of the artist, who viewed them as works in their own right. With the Opera, Degas was constantly experimenting, decompartmentalizing and reinventing creative art techniques.

“Elongated panels”

“Elongated panels”

Danseuses montant un escalier, entre 1886 et 1890

Musée d'Orsay

Legs du comte Isaac de Camondo, 1911

photo musée d'Orsay / rmn © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d'Orsay) / Stéphane Maréchalle / DR

See the notice of the artwork

In 1879, Degas began exploring an unusual format, that of the double square, in elongated compositions he called “tableaux en long”. The first of these, The Dance Lesson (Washington, National Gallery of Art), was shown at the Impressionist Exhibition of 1880. Many more would follow, up until the turn of the 20th century, each of which the artist constructs along a strong diagonal line, from one lower corner to the opposite upper corner, and their subject matter is invariably dancers in a rehearsal room, or jockeys on a racecourse.

Applying the principle of the frieze, which he studied as a young man through the great models, the Panathenaea friezes of the Parthenon and processions of Italian Quattrocento art, Degas takes this centuries-old model and severely skews its axis. The diagonal momentum he gives it energizes the principle of the frieze, and suggests to the eye of the beholder that the ballerinas and the thoroughbreds continue to run their course off the canvas.

Le foyer de la danse, 1890-1892

Washington, National Gallery of Art

© Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC / National Gallery of Art

Degas plays with notions of time (as if he were showing a single ballerina at various moments of a work session) and space (by setting these successive instants across the rehearsal studio). He is interested in the step-by-step aspect of motion in a way that recalls chronophotography as invented and popularized by Eadweard Muybridge and Etienne-Jules Marey. As formal laboratories for his work on movement and grace, the tableaux en long are modern friezes in which analysis of the gesture and momentum refers to both the science of seeing and the art of breaking down and representing.

Lighting effects and viewpoints

Lighting effects and viewpoints

La Loge, 1880

Houston, The Museum of Fine Arts

Photograph © The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston © The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Albert Sanchez, photographer

Degas had an abiding interest in the matter of lighting effects in theatres, onstage and on the figures that he depicted. An astute observer, he would make the occasional sketch of a given chandelier or gas lamp in a notebook. But what interested him most of all was the effect of light on bodies, and its place in the formal economy of the confined – and dark – space of the opera. Faces distorted by light beams coming up from the floor, emphasizing the features and almost putting a face mask on the singers and dancers; the role of the footlights setting apart the space of the stage and the house, being the boundary subscribers would step over in order to join their protégées; the visual power of contrasts of light and shade amid the scenery: the light, which the artist modulates at will, carves reality and undermines the terms of representation.

The bold viewpoints adopted by Degas reinforce the theatricality of such visions: views from an angle, from above, from below, boxes, stages, balconies; but also the actors and audience members are seen in a particular light, and reveal the play of glances which the opera-going public was familiar with and enjoyed.

Ballet, dit aussi L'Etoile, vers 1876

Musée d'Orsay

Legs de Gustave Caillebotte, 1894

photo musée d'Orsay / rmn © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d?RTMOrsay) / Hervé Lewandowski / DR

See the notice of the artwork

However, although theatre lighting technology was improving all the time during the 19th century, with gaslight replacing candles in the 1820s, later followed by the mid-century advent of the electric arc, Degas makes no real attempt to include an explicit description of these technical advances in his works. On the contrary, whether depicting the stage, watching behind the scenes or describing the bustle of the rehearsal rooms, he has an eye for sharp contrasts, dazzling backlighting and dancers’ silhouettes framed by the window behind them. The reality is sculpted by the light in these complex compositions in which the play of glances insists upon the power of perception in the representations we make of it.

Large synthetic drawings

Large synthetic drawings

Examen de Danse, 1880

Denver, Denver Art Museum

Don anonyme, 1941

akg-images © Photo courtesy Denver Art Museum / akg-images

After the last Impressionist Exhibition, in 1886, Degas concentrated on a limited number of motifs and compositions, which he drew in charcoal on large formats. Using tracing-paper, he could go over the same form to his heart’s content in different variations. In these large drawings, he produced a synthesis of the female body: far from the analytical vision that focusses on detail, he seeks to express the movement and rhythm of dancing bodies by means of “prodigiously balanced lines” (Gauguin).

These drawings have always bothered the critics, ever since they first came to public notice at the studio auctions in 1918, and still do so to this day, on account of their fierceness, not to say coarseness. They have been seen as going counter to the “Ingresque” Degas of the early days and as vehement testimony to the artist’s struggle to cope with his failing eyesight, whereas our 21st century view rather sees works of extraordinary modernity and great boldness in shaking off all conventions.

Danseuse au bouquet, saluant sur la scène, en 1878

Musée d'Orsay

Legs du comte Isaac de Camondo, 1911

photo musée d'Orsay / rmn © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski / DR

See the notice of the artwork

It is always this same concern for perfection that guides the artist: like the painter Frenhofer staged by Balzac in The Unknown Masterpiece, he contrives to express the life of forms, the “living line”, at the cost of sacrificing the finished work, preferring to make multiple drawings as a great open work, or sequences of a film in slow motion, rather than produce a work “cast in stone” in a succession of masterpieces. At a time when Symbolism was becoming the new avant-garde and again honouring Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and Gustave Moreau, Degas was drawing increasingly from memory, giving free rein to his recollections and his fancy: in his own words, “freed from the tyranny imposed by nature”.

“Orgies of colour”

“Orgies of colour”

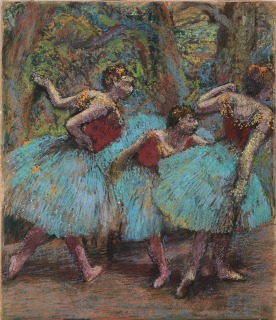

Trois danseuses (Jupes bleues, corsages rouges), vers 1903

Bâle, Suisse, Fondation Beyeler

© Robert Bayer

In 1899, Degas invited Julie Manet into his studio to see “some orgies of colour that I am doing just now”, which touched Berthe Morisot’s daughter all the more because “he never shows what he is doing”, as she records in her Diary. At the turn of the century, Degas focussed on his two preferred media, charcoal and pastel. With pastel, he could draw directly in colour and handle his sensual material with no need for a tool.

While he also did pastel drawings of milliners, jockeys, landscapes and nudes, dancers remained his favourite subject. He would draw them backstage, tirelessly rehearsing the same gestures, turning them into multiple figures like so many facets of the same woman viewed from various angles, borrowing his viewpoints from the art of sculpture and chronophotography.

He also drew them on stage, dancing in imaginary landscapes resembling real landscapes, these “states of eyes” which were among the only works that the artist was putting on public show at the time.

Danseuse au bouquet saluant, vers 1895-1900

Norfolk, VA, Chrysler Museum of Art

Don de Walter P. Chrysler, Jr., en mémoire de Della Viola Forker Chrysler

Chrysler Museum of Art © Ed Pollard, Chrysler Museum of Art / Ed Pollard

Degas returns to the same compositions in different, totally unreal colours, where all that matters is the visual liveliness, harmony or stridency. Casting propriety to the winds, he strikes the most unusual and daring chords. Always eager to experiment, he renews the art of pastel by working in layers and using fixative in order to stabilize each layer as a medium in its own right, while also playing on matt and glossy effects. In pastel, that “pollen of colours" (Lucie Cousturier), Degas found the ideal material and technique to express the wondrous aspect of the ballet, “this art in which the human body becomes the instrument of a magical celebration”.