Edvard Munch. A Poem of Life, Love and Death

Soirée sur l’avenue Karl Johan, 1892

Dag Fosse / Dag Fosse / KODE

The aim of this exhibition is to demonstrate the breadth of the artistic output of Edvard Munch (1863-1944) by exploring the entire course of his sixty-year-long career in all its complexity. Munch’s painting occupies a unique place in artistic modernity, plunging its roots in the 19th century to find its full expression in the next century.

His work as a whole, from the 1880s until his death, reflects a vision of the world characterised by a powerful symbolic dimension. The exhibition is not organized chronologically; the premise is to offer a global reading of his work focusing on its strong sense of unity.

In this respect, the notion of a cycle holds the key to understanding his painting. Munch often expressed the idea that humanity and nature are united in the cycle of life, death and rebirth. This vision is apparent in the actual construction of his work, in which certain motifs recur on a regular basis. The exhibition offers the opportunity to discover this artist’s world, which is cohesive and even obsessive, yet

constantly renewed.

From the intimate to the symbolic

“We want more than a mere photograph of nature. We do not want to paint pretty pictures to be hang on drawing-room walls. We want to create an art that arrests and engages, an art created of one’s innermost heart.”

— Journal, 1889

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Sophie Crépy

Edvard Munch (1863-1944) had no formal art training in his youth. As a child, he drew and painted with his aunt, Karen Bjølstad, who raised him after the premature death of his mother. At the age of seventeen, he studied for several months at the Royal School of Art and Design in Oslo, which was called Kristiania then, and exhibited for the first time two years later. In 1885, he was awarded a scholarship which allowed him to make his first trip to Paris. There he was able to see for himself naturalist works popular with Norwegian painters. He was also interested in the impressionists, who were causing a scandal in France at the time. He adopted their rapid painting style and free treatment of colour. Munch very swiftly moved away from landscape painting in favour of sensitive portraits of relatives, notably his sisters Inger and Laura, or friends from the bohemian circle in Kristiania gravitating around the writer Hans Jæger. The symbolic aspect of these intimate scenes was decisive in the early 1890s, and brought a singularity to his work.

The Frieze of life

“The Frieze of life is intended as a number of decorative pictures, which together would represent an image of life.

The Frieze is intended as a poem of life, love, and death.”

— The Frieze of Life, 1919

© Sophie Crépy

Early public exhibitions of Munch’s work were met with criticism or surprise. Keen to be understood, the painter devised a new way of presenting his art in order to highlight its rigorous cohesion. He grouped his main motifs together in a huge project which he eventually entitled The Frieze of life. This series of paintings, on which he began to work in the 1890s, featured in several major exhibitions. The Berlin Secession exhibition in 1902 was the key milestone: for the first time, Munch designed the hanging scheme for his works as a true discourse, stressing the continuous cycle of life and death.

He situated this project very firmly at the centre of his work and believed it encapsulated his entire career. He spent his whole life working on the component paintings and exploring their potential. Between 1900 and 1910, he also turned

to projects associated with the theatre and architectural decoration and incorporated some of these themes into them.

Waves of love

“I symbolised the connection between the separated couple with the help of the long wavy hair. The long hair is a kind

of telephone wire.”.

— Draft of a letter to Jens Thiis, circa 1933-1940

© Sophie Crépy

In parallel with his paintings, Munch produced versions of motifs from The Frieze of life in numerous drawings and engravings. He began to exhibit them on an equal footing as his paintings, integrating them fully into his discourse in 1897 in Kristiania and in 1902 at the Berlin Secession exhibition. This room is structured around the sentimental or spiritual bond uniting human beings which Munch symbolises by women’s hair, which can bind, attach or separate. This motif is virtually embodied in its own right, expressing relationships between characters in tangible form and making their feelings visible.

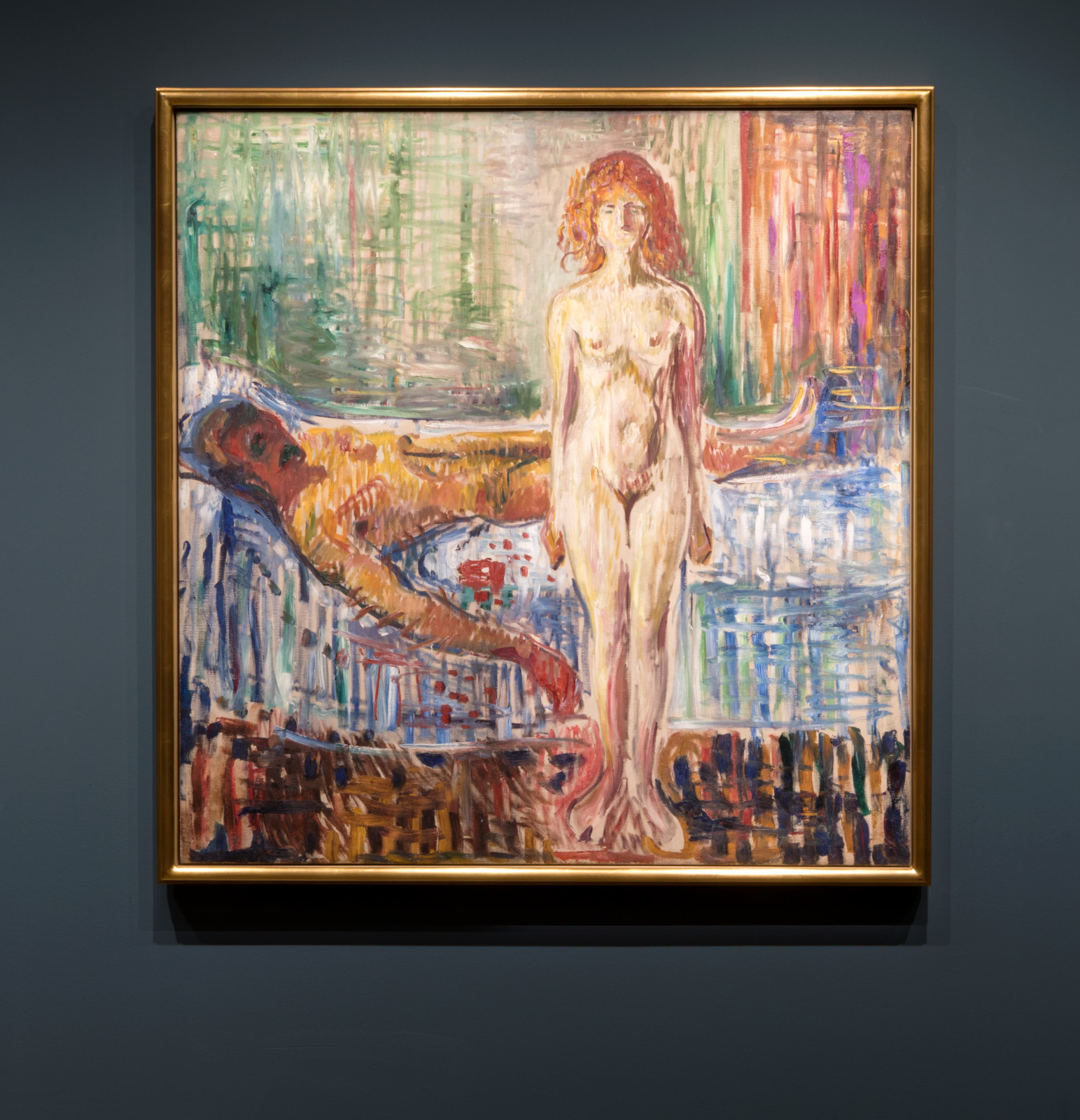

In his depiction of love, the artist projects a complex and always ambivalent vision of women. For Munch, figures which exude sensuality are always a source of danger or potential suffering. Although his Madonna is an icon, a focus for devotion, he nevertheless associates her with the macabre.

Re-use and mutation of the motif

There was always progress, too, and they were never the same – I build one painting on the last.”

—Draft of a letter to Axel Romdahl, 1933

© Sophie Crépy

Munch, like many artists of the era, practised the art of the reworking. He produced different versions not only of motifs but also of the general composition of his works, to such an extent that many of his paintings and engravings can be considered variants of previous works. Far from confining this practice to purely formal issues, he integrated it fully into the cyclical nature of his work. The shared elements of compositions were a vehicle for continuity between works, irrespective of the date of their creation or the technique employed. Furthermore, this art of creating variants allowed him to get closer each time to the emotion he was attempting to arouse.

By producing multiple versions of his works, he was able to retain a tangible record of his creations as a crucible for future works. In order to disseminate his work more widely, Munch learned the art of engraving in the mid-1890s. This medium opened up enormous scope for exploration and he quickly mastered traditional techniques to produce ever more expressive works.

Drama in camera

"Not a single picture has left behind an impression comparable with a few pages of an Ibsen drama."

— Letter to Olav Paulsen, 14 December 1884

© Sophie Crépy

Munch regularly addressed the work of contemporary playwrights, which he viewed as a source of literary inspiration, and was interested in modern staging and its relationship with the dramatic space.

His first experiences with the world of theatre began in 1894 when he met Aurélien Lugné-Poe, the director of the new Théâtre de l’Œuvre. During a trip to France, he produced illustrated programmes for the plays Peer Gynt and John Gabriel Borkman by the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen in 1896 and 1897.

Ten years later, Munch became involved in the production of a play, launching a true collaboration with a director. Max Reinhardt, the German founder of the Kammerspiele theatre in Berlin, who forged a new relationship between the stage and audience, approached him to create elements of the set for Ghosts, another play by Ibsen. This collaboration continued with the tragedy Hedda Gabler. These experiences had an immediate impact on Munch’s work. His approach to the construction of space was very clearly transformed, notably in the tightly focused series The Green Room in 1907.

Staging and introspection

“Sickness, madness and death were the black angels

that kept watch over my cradle.”

— Notebook, undate

© Sophie Crépy

Certain themes from the theatre of Henrik Ibsen and the work of Swedish playwright August Strindberg, such as solitude and the impossibility of romantic relationships, are directly reflected in Munch’s pictorial universe.

He even went so far as to borrow specific scenes from their plays in the staging of some of his self-portraits. He depicts himself several times in the guise of John Gabriel Borkman, an Ibsen character confined to his room for years at a time, and plagued by obsessive thoughts. This identification is all the more significant

as the artist lived in virtual seclusion from 1916, when he moved to Ekely, south of Oslo.

Munch’s self-portraiture was not restricted to interacting with the medium of drama. Looking beyond pure introspection per se, it expresses elements of the artist’s relationship with other people and the world, wavering between engaging with the outside world and retreating into himself. Munch’s portraits, which were often enhanced with an allegorical dimension, also express his acute awareness of the pain of life, the difficulties of creation, and the inevitability of death.

Monumental decor

« “It was I, with the Reinhardt frieze thirty years ago, and the aula and the Freia frieze, who launched modern decorative art.”

— Letter from Munch to the Oslo workers’ community, 6 September 1938

© Sophie Crépy

In the early years of the 20th century, Munch worked on several major decorative cycles and addressed the issue of monumental painting. The iconographic programmes which he developed were fully aligned with his own thinking

and incorporated themes which could already be found in his works.

In 1904, he was commissioned by his patron Max Linde to produce a series of paintings for his children’s bedroom. He revisited key subjects from The Frieze of life and added some more direct references to nature. The works were eventually returned by Linde, who reluctantly deemed them to be unsuitable.

Between 1909 and 1916, Munch entered a national competition organised to mark the centenary of Norwegian independence and produced his major decorative architectural work: a decor for the ceremonial hall of Kristiania University.

Munch’s international reputation was at stake in this project with a political agenda. It would take many years and several attempts before he won over the jury with his final design, which is still in situ today.

Exploring the human soul

“One shall no longer paint interiors, people reading and women knitting. They will be people who are alive, who breathe and feel, suffer and love. I would create a number of such pictures. People would understand the sanctity and power of it and would take off their hats as in a church.”

— Notebook, 1889-1890

© Sophie Crépy

The three works displayed in this room set the tone for the key feature of Munch’s work for several decades: the exploration and expression of the major emotions of the soul – love, anguish and existential doubt. Throughout his life, he returned almost obsessively to a small number of themes whose meaning he reworked constantly, thus marking the development of his painting towards symbolism in the early 1890s.

Puberty occupies a unique space in Munch’s painting. It launches a major investigation in his work into the transition between two ages, and the instability which characterises pivotal moments in life. In Despair, the painter offers us, with rare intensity, a key to understanding his work: the projection of human feelings onto the natural environment. Lastly, in The Sick Child, a reminiscence of the premature death of his older sister, he states the universal vocation of his works, exceeding by their force the evocation of a personal event.