New York and Modern Art. Alfred Stieglitz and His Circle (1905-1930)

The City of Ambition

Musée d'Orsay

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

See the notice of the artwork

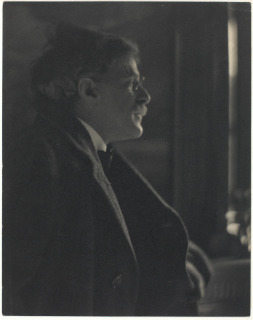

Portrait d'Alfred Stieglitz, vers 1918

Musée d'Orsay

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

See the notice of the artwork

The youngest son of German immigrants, Stieglitz was born in 1864 and spent his childhood in New York where his parents owned a house. In 1882, his father decided to sell his prosperous clothing business in order to settle in Europe with his family. Stieglitz thus discovered and developed a passion for photography in Berlin, where he pursued his studies to become an engineer.

With determination and perfectionism, Stieglitz went to great lengths, even attending chemistry classes, to master the technical aspects of the art.

Stieglitz at the time belonged to the Pictorialist movement, born in England in the 1880's. It proclaimed the artistic character of photography, and can be split into two main trends: the first defended an idea of photography that imitated painting and engraving through manipulation of the pictures or the choice of fantastical or mythological themes; the other promoted a naturalistic vision of photography.

Stieglitz identified himself with the latter. He chose to root his subjects in reality, believing that any artistic quality lay in the operator's outlook on the world around him.

In Europe, Stieglitz wrote articles, took part in competitions, exhibited and was awarded numerous prizes. When he returned to live in New York in 1890, he was already a crucial figure of Pictorialist circles and the experience he acquired allowed him to become quickly one of the most striking personalities of New York's cultural scene.

Springs Showers, 1900-1901

Chicago, Art Institute, Collection Alfred Stieglitz

© Art Institute of Chicago

Back in New York, Stieglitz took many views of the city. In order to soften the focus, he enlarged and reframed an internegative and used a coarse-grained paper for the print, a process characteristic of Pictorialist aesthetics. In 1896, he participated in the founding of the New York Camera Club and the following year he took the direction of the club review Camera Notes.

In 1902, he founded the group Photo-Secession, together with Clarence White, Gertrude Käsebier and Edward Steichen (three of the most gifted pictorialist photographers in the United States), amongst others. Photo-Secession found inspiration in the example of the Munich and Viennese secessionist associations.

The group's ambitions included: the promotion of pictorialist photography; the organisation of Americans who either practised or were interested in the arts; and the staging of exhibitions, not necessarily devoted exclusively to members of the Photo-Secession.

In 1903 the first issue of Camera Work, a luxurious review created by Stieglitz to give a wide circulation to the group’s production, was published. Camera Work was characterised by its being open to other forms of arts – literature, music, contemporary visual arts - and by the extreme care given to the quality of reproductions, using the technique of photo-engraving. Camera Work was deliberately turned towards the European avant-garde.

In 1905 The Little Galleries of Photo-Secession opened in New York and were soon to become famous among both artists and intellectuals as a laboratory of modern art.

Enfer, vers 1900-1908

Paris, Collection André Bromberg

© Collection André Bromberg, Paris, 2004

The small exhibition space The Little Galleries of Photo-Secession, soon to be nicknamed "291" as they were located at number 291, Fifth Avenue, quickly prevailed as a crucial cultural venue in a New York that was then undergoing deep transformations. The city progressively established itself as the cradle of American modern art and became a pole of attraction for European artists.

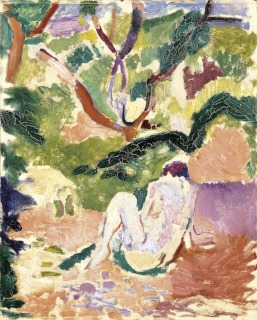

The orientation of the gallery, which at first showed exclusively photography, started to evolve as early as 1908. In January of that year, Stieglitz exhibited drawings by Rodin: stunning studies of nude figures that marked contemporary minds. The public of "291" was later to discover Matisse, whom Stieglitz was able to endear to the American public after three exhibitions, and Cézanne, whose influence is noticeable in the works of young American painters whose work Stieglitz also exhibited.

Nu dans les bois, 1906

Brooklyn, Museum of Art

Don de George F. Of

© Sucession H. Matisse, 2004

At this point Steichen played a central part in the activities of "291". Thanks both to his residence in France from 1908 up to the First World War, and to his activity as advisor and impresario, close contacts were established between the European avant-garde and "291". He also secured loans for exhibitions.

The exhibitions programmed between 1908 and 1910 reflected Stieglitz and Steichen's conviction that it was necessary to alternate avant-garde and more classical artworks, photography and other arts. This innovative interdisciplinary connection contradicted the established hierarchy by instituting equality between photography and traditional arts.

"291" came to fulfil amply the laboratory role Stieglitz wanted. The exhibitions provoked discussion on the new directions art could take. The idea that photography, rather than imitate painting, should seek its own identity was advanced by artists and critics connected with "291".

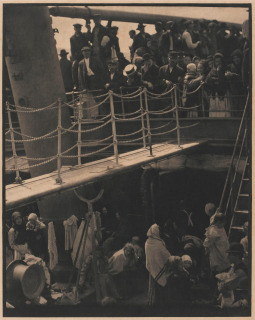

The Steerage, en 1915

Musée d'Orsay

Don de la Georgia O'Keeffe Foudation, 2003

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

See the notice of the artwork

In 1910, Stieglitz organised an important pictorialist international exhibition at the Albright Art Gallery, Buffalo. This was very successful and several museums acquired artworks of the Photo-Secession group.

Stieglitz's struggle for photography to be recognised as an art was thus rewarded.

Yet Stieglitz's prevailing position was not unanimously welcome. Several first-rank photographers, including Clarence White, Alvin Langdon Coburn and Getrude Käsebier, left Photo-Secession.

Avant-garde art served as catalyst for Stieglitz. In The Steerage, a famous shot taken in 1907 but in which he was only really interested from 1910 onwards, Stieglitz captured the crowding of working classes on an ocean liner. The picture was not reframed. Several elements in the decor – a funnel, a ladder and a walkway – give the image its structure around the spot of light constituted by the round and white hat worn by one of the passengers.

When showed The Steerage in 1914, Picasso exclaimed: "This man has understood what photography is about!"

From then on he was an adept of straight photography. After the First World War, many American photographers, including Edward Steichen, Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand (and later Edward Weston), adopted the same approach.

Although he was sometimes described as a rather static figure, Stieglitz 's photographic practice and artistic approach were in fact constantly evolving.

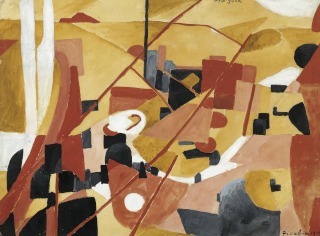

New York, 1913

Paris, Centre Pompidou, musée national d'Art moderne

© MNAM

In February-March 1913, the Armory Show, a famous contemporary art fair very remote from Stieglitz's approach, took place in New York. It was a far-reaching event, openly commercial, from which photography was entirely absent. Stieglitz chose to exhibit his own photographs at "291" at the same time. He then exhibited works by Picabia, the only French artist who came to the Armory Show to present his work: abstract compositions inspired by New York.

Following the Armory Show, the modern art market in the United States took off.

Import fees on artworks were reduced and galleries multiplied.

Stieglitz examined his own place in this world and possible future role, marking the beginning of a new period for "291".

Tête de femme, 1909

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Succession Picasso, 2004 - photo Metropolitan Museum of Art

Edward Steichen took part in the organisation of the Brancusi exhibition in 1914.

The exhibitions devoted to African art in 1914 and to Picasso-Bracque in 1914-1915 were organised by Marius De Zayas, a Mexican draughtsman who had already exhibited his caricatures at "291" as early as 1909. Stieglitz was also advised by Paul Haviland, a young French entrepreneur, Agnes Meyer, a journalist and finally Francis Picabia. They all sought to inject new dynamism into the gallery and reproached Stieglitz a certain immobility.

To give "291" new momentum, Stieglitz's collaborators suggested creating a new review and opening a new gallery designed as a commercial branch of "291". The latter agreed to both proposals.

Inspired by Apollinaire's review Soirées de Paris and financed by Stieglitz, the review 291 was published from March, 1915 to February, 1916 and replaced Camera Work during this period. It differed radically from the latter, in particular in its satiric tone.

On October 7, 1915 the Modern Gallery was inaugurated. It was managed by De Zayas, who organised important exhibitions, in particular on cubism. But it finally had to be closed in 1918.

Despite financial difficulties, Stieglitz managed to maintain "291" in activity until Spring 1917.

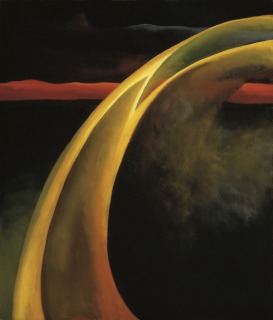

Orange and Red Streak, 1919

Philadelphie, Philadelphia Museum of Art

© photo Philadelphia Museum of Art

A few weeks before the gallery "291" closed in May 1917, Stieglitz proved that his provocative spirit was still intact. He exhibited Fountain by Marcel Duchamp, a urinal, presented anonymously, that had just been rejected from the exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists of which Duchamp was one of the founding members. But from then on, and even more so after the war, Stieglitz devoted much energy to support American artists, in particular Paul Strand and the young painter Georgia O'Keeffe, with whom he had an affair from 1918 onwards.

The First World War proved fatal to the gallery "291".

Stieglitz faced supply problems and could no longer rely on his wife's financial backing as her fortune was largely diminished due to the conflict. The last exhibition was devoted to Georgia O'Keeffe.

The publication of Camera Work was suspended the same year and the group Photo-Secession, already moribund since 1910, disbanded completely.

Rain, 1924

Washington, National Gallery

© DR - photo National Gallery of Arts, Washington

What is commonly referred to as "Stieglitz's circle", i.e. the artists who revolved around him and whom he supported directly, evolved during this period and was less open than before to the outside world. The new circle was comprised of a few writers and a small group of artists, exclusively American, who had already exhibited at "291". Stieglitz called them the "six plus x", namely himself, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Paul Strand and Georgia O'Keeffe. The seventh member varied but most often it was Charles Demuth. The group adopted esthetical and moral objectives: have a truly American art emerge that would be rid of European influences while struggling against the fundamentalism and materialism that threatened their country.

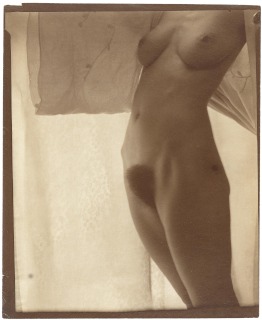

Georgia O'Keeffe, Torso, 1918

Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum

© photo J. Paul Getty Museum

In order to promote the artworks of artists belonging to this new circle, Stieglitz resumed his activities as gallery-owner. At first he occupied a section of the Anderson Galleries (1921-1925). He then opened The Intimate Gallery (1925-1929) and finally An American Place (1929-1946).

Stieglitz also exhibited his own photographs. He found new inspiration in his relationship with Georgia O'Keeffe and after the war his art underwent a genuine renewal. Between 1918 and 1937, he made analytic portraits of his companion. Her face and different parts of her body are detailed in a free expression of his desire. His approach was completely new in its form, a succession of close shots, and in the eroticism it emanates.

Stieglitz’s art became more introspective. In the park of his family property by Lake George, he rediscovered nature, which he photographed as fragments. He then started a series of shots of clouds which he entitled Equivalents, wanting to show "an external equivalent of what already took shape within my mind".

From 1927 onwards, New York skyscrapers provided him with the subject of a new series. He shot the pictures from his room in the Shelton Hotel, then the tallest building in New York, and from the windows of his gallery An American Place. The lively city of his pictorialist period gave way to a geometrical urban universe, glacial and inhuman.

Equivalent, en 1925

Musée d'Orsay

Don de la Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation, 2003

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

See the notice of the artwork

Before giving up photography in 1937 due to declining health, Stieglitz achieved what constituted, together with the Equivalents, a true spiritual testament. His last pictures were those of the trees by Lake George. He celebrated the renewal of Spring and contemplated himself photographing the old poplars on the verge of death.

After the First World War, the circulation of Stieglitz's work was fairly limited. He regularly exhibited but chose to publish relatively little.

When Stieglitz passed away in 1946, some of his photographs had already entered the collections of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

His struggle for the artistic recognition of photography was by then complete.

His intelligence and unprejudiced interest in different forms of art, painting, sculpture and photography made him a pioneer spirit and one of the personalities who brought about the birth of modern art in the United States.