Who's Afraid of Women Photographers? 1839-1945

Deuxième partie : 1918-1945

Portrait de Joan Maude, 1932

Londres, National Portrait Gallery

© Yevonde Portrait Archive / National Portrait Gallery London

Women Photographers ?

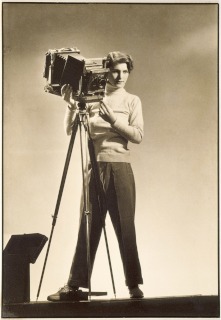

Self-portrait with camera (Autoportrait à la camera)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Los Angeles

© Digital Image Museum Associates/LACMA/Art Resource NY/Scala, Florence

Women Photographers ?

Being a woman photographer post-World War I involved conquering new genres and fields. It entailed contributing to the emergence of modern photography and being part of the creative ferment of the cultural hotspots of Paris, Berlin, Budapest, London, New York and San Francisco. Some of these women were now looking through the viewfinder, having previously been subjects for the lens.

Being a woman photographer was also about carving out a role in the theory of photography and in writing its history. Women photographers played an active role in the institutionalisation of the medium by organising exhibitions in salons and galleries, by setting up schools and running commercial studios or photo agencies. For women, photography was now a multifaceted profession with a multitude of applications.

Being a woman photographer was also about setting up training and mutual assistance networks against a backdrop of great social mobility on an international scale and keen rivalry with men. Shared spaces, titles and status gave rise to anxiety, tension and conflicts. Fellow male professionals, critics, historians, journalists, and even sometimes husbands, strove to paint these women, who were also blurring the boundaries of the traditional division of labour and gender roles, as rivals.

The exhibition tour, which leaves the confines of the studio and engages with the world, aims to show, against the backdrop of a ravaged Europe, how women embraced the photographic medium as part of an artistic and professional empowerment strategy and conquered territories which were previously the preserve of men. This journey through the history of modernity also aims to offer a modern perspective on history.

Subverting convention. Women’s handiwork

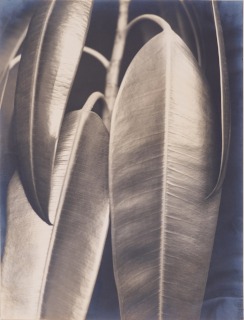

Gummibaum, vers 1927

Essen, Museum Folkwang

© Museum Folkwang Essen

Subverting convention. Women’s handiwork

In the period following World War I, how did women photographers approach genres such as portraiture, still life or intimate scenes, which were their traditional preserve in the 19th century? For many years they had specialised in these fields by default because they required patience, empathy and contact with models, or because they took place within the closed confines of the home or studio, yet they often subverted the conventions of representation in a critical or ironic way.

Shots of flowers and plants redolent with sensuality and flamboyant portraits of independent women suggested that women also experienced desire, just like men. Numerous pictures of dolls – symbols of the social reproduction of female roles – in damaged, broken or deformed guise, but rarely eroticised, and multiple photographs of duplicitous or grotesque men, hinted at the inklings of profound social and cultural change at work in Western societies. In many of their photographs, men’s arrogance is diminished and their dominance is challenged.

These women forged the stylistic and theoretical repertoire of modernity, experimenting, often as pioneers, with macrophotography (Laure Albin Guillot, Aenne Biermann), solarisation (Lee Miller, Lotte Jacobi, Gertrud Fehr), photograms (Lucia Moholy), light drawing (Barbara Morgan, Carlotta Corpron), multiple exposures, photomontage and photo collage (Olga Wlassics, Dora Maar, Marta Astfalck-Vietz), infrared and ultraviolet rays (Ellen Auerbach), and colour photography (Madame Yevonde, Gisèle Freund, Elisabeth Hase, Marion Post Wolcott). Their works played a major role in avant-garde movements such as Surrealism, New Objectivity, Straight Photography and New Vision.

Embryo, 1934, tirage 1955-1960

Keith de Lellis Gallery, New York

© Reproduced with permission of the Ruth Bernhard Archive, Princeton University Art Museum. © Trustees Princeton University © Photo courtesy of the Keith de Lellis Gallery, New York

Eulogies of the male body and forbidden games

Although women were forbidden from taking photographs of nudes in the 19th century, they now tackled this genre, stripped of literary, allegorical or mythological allusions. The naked female body, which escaped censorship as long as neither pubic hair not genitalia were visible and it resembled a monochrome statue, was often an obligatory rite of passage allowing male or female photographers to display their technical and artistic prowess. The male body, taken outside the context of naturism or sporting activity, was still a relatively taboo subject – especially when it was the focus of a woman’s aesthetic enjoyment.

Following in the footsteps of early 20th century American photographers, Imogen Cunningham and Adelaide Hanscom, Laure Albin Guillot was one of the first women in Europe to exhibit male nude studies.

Whatever the gender of the model, the boundaries between licit and illicit, legality and illegality, morality and immorality were shifting. In 1920, Danish photographer Mary Willumsen was arrested because her photos of scantily-clad bathers were felt to veer too far towards the erotic. The Berlin police confiscated prints exhibited in a gallery of dancer Claire Bauroff in the nude taken by Austrian Trude Fleischmann, on the grounds of “indecency”. German photographer Gisèle Freund, who took refuge in Paris to escape Nazi persecution, was investigated on several occasions by the police under (wrongful) suspicion of producing pornography in her studio.

Although pictures by Florence Henri, Germaine Krull, Ergy Landau and Dora Maar were displayed in many photography exhibitions and published in avant-garde journals, they also featured regularly in more lightweight magazines focusing on glamour and eroticism.

In the 1930s in Paris alone, there was a proliferation of publications (Paris Sex Appeal, Paris Magazine, Pages Folles, Vénus Magazine, Pour lire à deux) often with very large print runs, which offered an outlet for their photos and therefore provided them with a regular source of income.

What is “Femininity”?

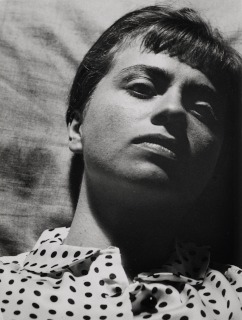

Self Portrait, 1933

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Los Angeles

© Digital Image Museum Associates/LACMA/Art Resource NY/Scala, Florence

What is “Femininity”?

In his account of the huge exhibition “Femmes artistes d’Europe” at the Jeu de Paume, published in L'Officiel de la couture et de la mode de Paris in April 1937, the critic S.R. Nalys said of the women photographers represented there: “Brutal men brandish the lens like a machine gun. However, women handle it tenderly, having first caressed with their eyes the subject they intend to focus on. There is a gulf between the two approaches: femininity.”

Society magazines reflected stereotypical views of “female” traits in the field of photography and promoted a vapid and superficial imaginary realm, prioritising pictures stripped of any political content (landscapes, still lifes, animals) or in a traditional mould. However, many women photographers viewed their situation with the benefit of critical distance in their pictures, highlighting its contradictions.

They expressed in frank terms the violent nature of the relationship between the sexes and the straitjacket of marriage. Some women who challenged social norms, such as Claude Cahun, Germaine Krull, Hannah Höch and Lisette Model, also explored the possibility of alternative sexual orientations.

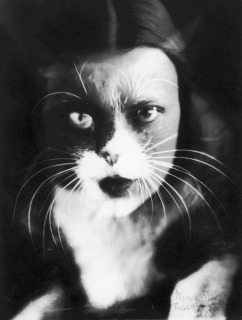

Me + Cat, 1932

Florence, Alinari museum

© Archives Alinari, Florence, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Wanda Wulz

Self-portraits and disguises

Exploring genre, exploring gender Since the dawn of photography, attempts at selfrepresentation have been made using mirrors, shutterrelease cables and self-timers.

However, self-portraits of women in the 19th century are scarce. It was not until the 1920s that baring one’s body, disguises and blurring of identities became favourite subjects. The pre-requisites were financial security and access to “a room of one’s own” in the words of British writer Virginia Woolf in her 1929 essay: a free and intimate locus in the private space or in a professional studio.

Disguises and staged self-representations were very popular with women. The mirror and the lens were more than just the objects of optical curiosity which they represented for men. They were a medium for introspection, exploring identity and sexuality and distancing oneself from the social associations of the traditional roles of daughter, spouse and mother.

The extraordinary growth in female self-portraiture was paralleled by the emergence of the new woman epitomised by this new generation, with her bobbed hair, boyish trousers and short skirts, striking bold poses, hand on hip or holding a cigarette. Women photographers reinvented themselves by (de)constructing their image, although not without a degree of ambivalence, uncertainty and anxiety.

Their choices of names or pseudonyms as artists were part of this process of emancipation. Dorothea Lange and Margaret Bourke-White adopted their mothers’ maiden names; Rogi André, Lotte Errell and Laure Albin Guillot took their husband’s first name as a patronymic; Gerda Taro restyled herself as a copy of the equivocal Greta Garbo, and Marie-Claude Vogel became the enigmatic Marivo. Claude Cahun opted for a gender-neutral first name and Lee Miller chose a masculine first name.

I am a photographer

Das Atelier in der Kugel gespiegelt (Selbstportrait im Atelier, Bauhaus Dessau), 1928-1929, tirage en 1990

Berlin, Bahaus Archiv

© Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

I am a photographer

A self-portrait depicting a woman as a photographer is a type of visiting card designating her professional status. It is an expression of technical and aesthetic intent. However, it is not merely the counterpart of the male self-portrait. In a gesture of self-assertion, using the camera to extend the scope of their vision, women became “gazing subjects”, defying centuries of stereotyped iconography. Whether they were intended for distribution or for the private realm, these self-portraits enhanced women’s social and symbolic visibility.

Some female exponents broke into the public sphere and also achieved recognition through publication. The interwar period was a time of intense ontological thought about this medium. Moving beyond correspondence and private diaries, some of these women embraced written forms previously monopolised by men, including manifestos, textbooks and histories.

Works by women such as Dorothy Norman and Lee Miller were the fruit of intellectual or emotional affinity with acknowledged masters (Alfred Stieglitz, Man Ray), whose biographers they became. Others, including Madame Yevonde, Margaret Bourke-White and Gertrud Fehr, told the story of their introduction to the medium which offered them public recognition and independence.

The manifesto, a form which turns writing into action and is designed to express an agenda, was also adopted by Dorothea Lange, Germaine Krull and Tina Modotti. For their part, Laure Albin Guillot and Berenice Abbott published textbooks with experiments and advice aimed at students and trainee photographers. Lastly, Gisèle Freund and Lucia Moholy were strongly influenced by the model offered by the social sciences and breathed new life into the history of photography.

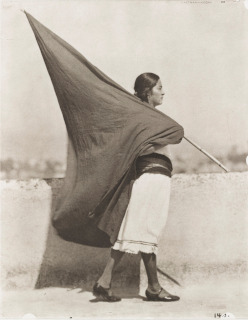

Woman With Flag, 1928

New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

Courtesy of Isabel Carrbajal Bolandi

© 2014, Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence

Conquering photographic territories. Male bastions

In the first half of the 20th century, women conquered every realm of the (male) world in large numbers. They took control of genres which had previously been taboo, such as the nude, and erotica and the sexual representation of the body more generally, vying with men in the emerging picture markets: fashion and advertising, reportage and journalism. Armed with their cameras, they penetrated the world of politics, travelled to theatres of war, and ventured solo to exotic climes. Their status as photographers provided an entrée to areas previously rarely frequented by women, or even barred to them.

The rise of the illustrated press, which was facilitated by new photomechanical processes, meant that fashion and advertising offered women professional outlets and financial independence. Hundreds of illustrated publications, factual periodicals and specialist journals published their visual experiments in a field where the rules were still being written.

Women’s magazines were aimed at a modern readership and presented pictures of emancipated women, sometimes produced by other women, and often depicting independent lives.

Some of these women photographers also deliberately adopted symbols traditionally viewed as male: machines, motor cars and industrial architecture. In this way, they addressed iconic objects whose beauty was celebrated in avant-garde circles, such as the Eiffel Tower or the Marseille transporter bridge, demonstrating both technical mastery and aesthetic skill.

New horizons and inner journeys

Descente du col de Djengart à la frontière de la Chine. Kirghisie

Lausanne, Musée de l'Elysée

© Musée de l'Elysée, Lausanne /Fonds Ella Maillart

New horizons and inner journeys

American explorer Harriet Chalmers Adams, despite being a frequent contributor to the National Geographic, was barred from entry to the exclusively male club that was the National Geographic Society. With the help of her associates, she founded the Society of Women Geographers Geographers in Washington in 1924.

Female traveller photographers were frequently denied access to sporting expeditions or scientific missions because of their gender. Ski and sailing champion Ella Maillart was not allowed to join the Yellow Crusade car rally from Beirut to Peking organised by André Citroën from April 1931 to February 1932. In 1934, Commander Charcot refused to admit oceanographer Odette du Puigaudeau to his station at Scoresby Sund, in Greenland.

Building on the experience of pioneering 19th century women explorers, a generation of cultured women braved foreign climes, inspired by romantic travel literature which was extremely popular in the early 20th century, but also sensitive to the emerging ethnological approach. As journalists, writers, and researchers they used photography and film as recording instruments, as tools to analyse the societies they encountered, as well as a means of emancipation and self-discovery.

Distance was conducive to greater autonomy. It provided an opportunity for freedom and alternative social relationships, and extended the hope that they could abolish their status as women in the form in which they experienced it in Europe or the United States.

Maquisards des Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur (FFI) près de Venelles à Sainte-Victoire, 1944

Paris, Musée de l'Armée

© DR- Musée de l'Armée, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Marie Bour

In the front line

The 1930s saw the rise of the photojournalist: a photographer who addresses a subject in pictures with text (possibly self-penned) for the press.

Women joined the ranks of this emerging market in a variety of roles – as freelancers negotiating their own prints or working through the intermediary of a photo agency; as regular contributors to a magazine, like Germaine Krull for Vu and Lee Miller for Vogue ; and as permanent staff on an editorial team, like Margaret Bourke-White and Hansel Mieth at Life.

Although the commercialisation of smallformat, very easy to handle cameras such as the Ermanox (1924), Rolleiflex (1929) and Leica (1930) facilitated the growth of photojournalism, it was also the desire to see everything, go everywhere and address every issue which drew women out of the studio and into public places and the political arena, hitherto monopolised by men.

American Toni Frissell decided to forsake the inside pages of the fashion magazines for which she worked, to prove that she could deliver front cover-quality reportage. In 1941, she offered her services as a photographer to the Red Cross, the Eight Army Air Force and the Women's Army Corps.

About dozens women from each country received accreditation and commissions to cover World War II. Armed conflict was the last remaining male bastion to conquer. For many of these women, the camera became a weapon, a means of offering resistance, defending shared values and fighting for freedom.

Women photographers, women film-makers

Women photographers, women film-makers

Some of these women explored other forms of creativity and expression alongside photography: painting (Dora Maar, Marta Hoeppfner), writing (Claude Cahun, Eudora Welty), design (Marianne Brandt), music (Florence Henri), etc. They also worked in film which, like photography, was a recording medium and a repository for story-telling, enhanced with sound and movement.

In the period 1920-1930, the appearance of 16mm sub-standard film and the development of portable cameras fostered technical and aesthetic experimentation (Germaine Dulac, Germaine Krull, Maya Deren), as well as geographic and cultural mobility (Thérèse Rivière, Margaret Mead, Ella Maillart, Ria Hackin). The lack of existing structures in this field – cinema was only born in the 1890s – and the absence of obligatory training bodies made working in this medium easier for amateur film-makers, male and female.

All films are made to be screened and therefore address a potential audience. The western world was seething with tension and anxiety and women engaged in public debate. They strove to change society armed with cameras: some worked on behalf of totalitarian regimes – Nazi (Léni Riefenstahl) or Soviet (Margaret Bourke-White) – some supported the Zionist project (Ellen Auerbach), and others promoted the ideals of peace between nations (Madeline Brandeis) or solidarity with the impoverished (Ella Bergmann-Michel). The use of film undoubtedly set the seal on women’s entry to the political sphere.